I have written a lot over the years concerning de-escalation. I believe it is an extremely important skill to learn and develop as most acts of aggression/violence are a result of social interactions. Whilst we may spend a lot of time and effort devising personal safety and protection strategies to reduce the risk of being targeted by persistent and hardened offenders (which isn’t a bad thing), we may do so at the expense of thinking about and training to deal with the more likely aggressive incidents involving everyday social interactions e.g., we are far more likely to get into an argument/dispute over a parking space, jumping a queue, or cutting someone off etc., than being involved in a pre-planned/premeditated street robbery, car-jacking or abduction. When thinking about and dealing with violence there is often a tendency to focus on the extreme, rather than the more common and likely events involving disgruntled, frustrated and/or annoyed individuals; people who have often become too aggressive, too fast, over what are at the end of the day minor and unimportant events. Incidents, which can often catch us by surprise/unawares because from the non-emotional/rational perspective they don’t appear to warrant the emotional depth/importance that the other person is giving to them e.g., we don’t recognize that the other individual may be prepared to use lethal force in order to “punish” us for taking what they believe is their parking space etc. Most of these types of incidents can be successfully dealt with using de-escalation strategies – only the most emotional and volatile individuals won’t want to be given an exit route from being involved in a physically violent confrontation. Whilst I have written and presented a lot on the verbal component of de-escalation, I haven’t written so much on the physical aspect of de-escalation, other than talking about the need to have a certain stance etc. In this article I want to look at different types of range and space, relative body positioning and how/when to make eye-contact.

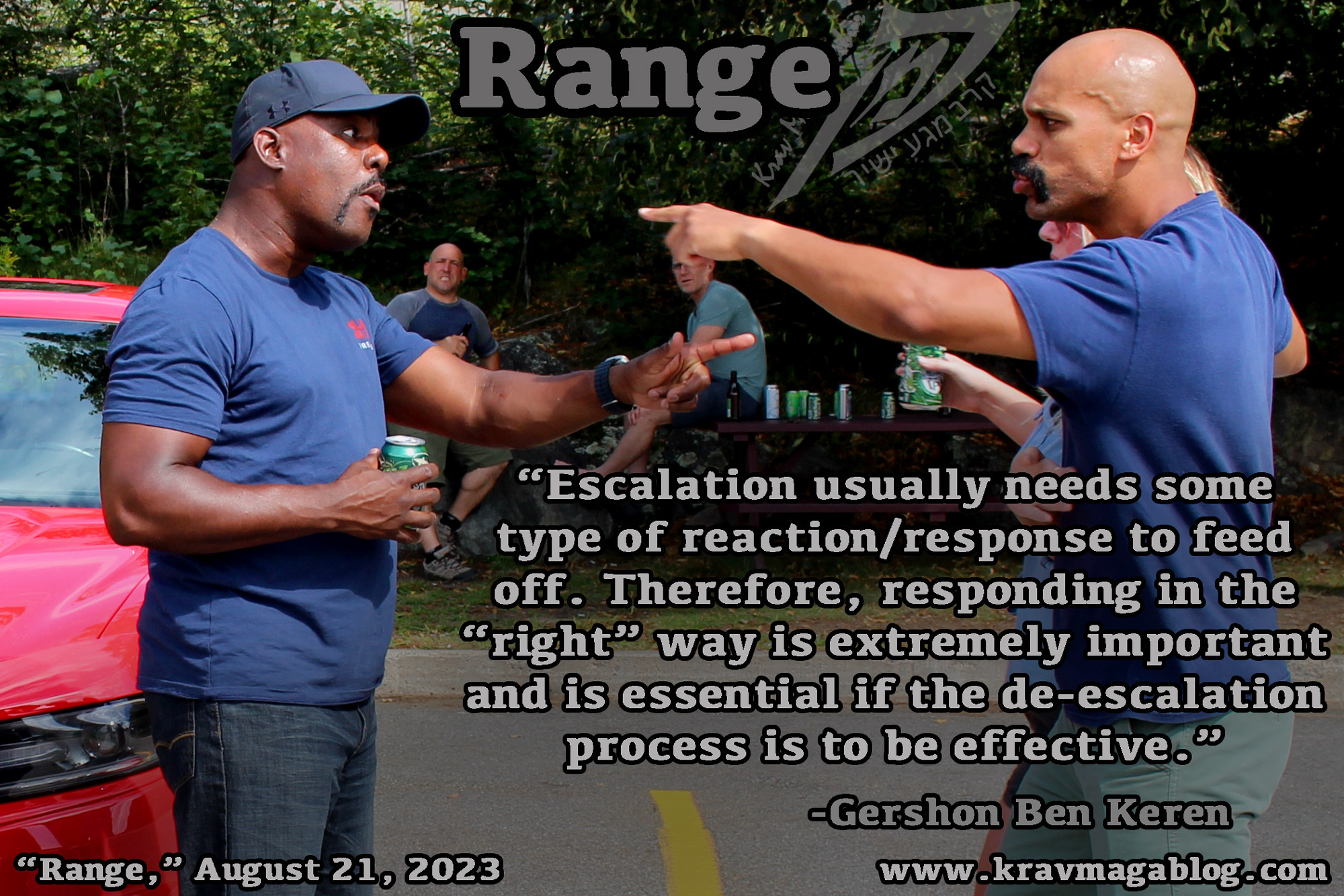

The first thing to understand about de-escalation is that there isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution and that it is a process which requires a certain level of adaptability. It is often useful to think about de-escalation from the perspective of escalation i.e., what would make the situation worse. When situations escalate it is often around 30% due to the aggrieved/disrespected/frustrated individual, and around 70% due to the reaction of the other person. This reaction could be one of fear, panic, and/or confusion etc., rather than an overly aggressive and challenging response. Escalation usually needs some type of reaction/response to feed off. Therefore, responding in the “right” way is extremely important and is essential if the de-escalation process is to be effective. Part of an effective response is to understand how we understand space and distance, and ways to control range effectively, so that we appear engaged but not challenging. There are four types of “space” that we need to understand how to use. These are:

Intimate Space

Personal Space

Social Space

Public Space

Often when people become aggressive towards us, they invade our intimate space; they get up in our face. Violence isn’t just personal, it is intimate. We can think about “Intimate Space” as being that between our elbow and our shoulder (if the arm is stretched out in front). At this distance and range, if someone were to make an attack it would be almost impossible to protect ourselves. We wouldn’t have time and space to cover, let alone block. Whilst we remain in this space, we are both at risk of physical attack, and also presenting a challenge and potential threat to the person we are dealing with i.e., we aren’t seen to be “backing down”, even if we are wanting to avoid a physical altercation. Personal space can be measured as being between the fingertips and elbows of an outstretched arm. Being within someone’s personal space means we will still be perceived as a threat, and so we should move into what is termed “Social Space”. Social space is measured as being just outside someone’s outstretched arm e.g., if someone wanted to punch, grab, or push another person etc., they would first have to move forward to do so. However, because de-escalation involves engaging with the other person we don’t want to move too far back as this puts us in what is referred to as “Public Space”. If/when we are in public rather than social space, we are signaling that we don’t want to interact with the other person. This can be seen as ignoring, discounting, and/or devaluing the other party’s grievance, which is likely to escalate things. Trying to walk away from an aggrieved person, even if you believe their grievance is unwarranted, is only likely to make things worse. When you ignore someone, you devalue both them and their experience(s). This is why it is key to occupy the “Social Space” where you can engage with them.

It is also important to angle yourself slightly off-line, rather than “square off”, facing your aggressor directly. This accomplishes a few things. It means that your aggressor will have to re-align themselves before making an attack, increasing your time to physically react/respond, as well as presenting yourself in a non-physically challenging position. Although you will want to be in a position to make contact, if you can present yourself as wanting to listen first – averting your gaze somewhat by leaning your head slightly to one side – this can indicate that you are taking what the other person says seriously. When you are ready to speak in response, this is the time to make eye-contact. This is a subtle way to demonstrate that you are trying to understand the other person’s grievance, instead of challenging it. Obviously, if the person is already at such a heightened emotional state where their only thought is to cause you harm, such subtleties will be lost, and your range and positioning are there to best prepare you for a physical confrontation.

Effective de-escalation involves using both physical and verbal skills to diffuse the emotion from an incident. How you compose yourself and what you say (often more important than the way you say it) is important in de-escalating verbally aggressive, and potentially violent, incidents. Not only should your physical positioning appear confident and non-threatening, it should also put you in the best position to defend yourself whilst putting your aggressor in a disadvantaged state.

Share:

Gershon Ben Keren

2.8K FollowersGershon Ben Keren, is a criminologist, security consultant and Krav Maga Instructor (5th Degree Black Belt) who completed his instructor training in Israel. He has written three books on Krav Maga and was a 2010 inductee into the Museum of Israeli Martial Arts.

Click here to learn more.