I last week’s article I looked at some meso-level (middle level) Boston crime hotspots,

concerning street robberies/muggings and drug offenses, and how both types of crime were

basically found in the same general areas. In this article I want to look specifically at

personal/private theft hotpots to examine how these differ and look at some of the reasons that

allow such hotspots to get created. In next week’s article I want to look at auto theft in Boston

and how this differs between different types of vehicles along with the seasonal/temporal

aspects and the way these effect crime hotspots.

The terms theft, larceny and stealing are basically/colloquially acts where an individual

takes/removes another person’s property with the intent of permanently depriving them of it.

They differ from robbery in that no force or threat of force is used e.g., if a person picks your

pocket, or breaks the lock off your bike and then rides off on it, there was never a real or implied

risk that you’d get hurt or injured in the process. This can sometimes make it difficult to

determine whether a bag or purse snatch constitutes a theft or a robbery, as some degree of

force may be used in taking it from its rightful owner. A useful measure to determining which

offense the incident should be classified as, is to determine whether an excessive amount of

force was used for the offender to obtain it e.g., did they unnecessarily push the victim, rather

than simply grabbing the bag etc. As pointed out last week, the datasets used to create these

heatmaps are based off of BPD (Boston Police Department) incident reports for 2015 to 2022;

although I have incident reports predating 2015, in 2015 there was a change in the reporting

software used, and the “old” classification codes aren’t easily transferable to the new system.

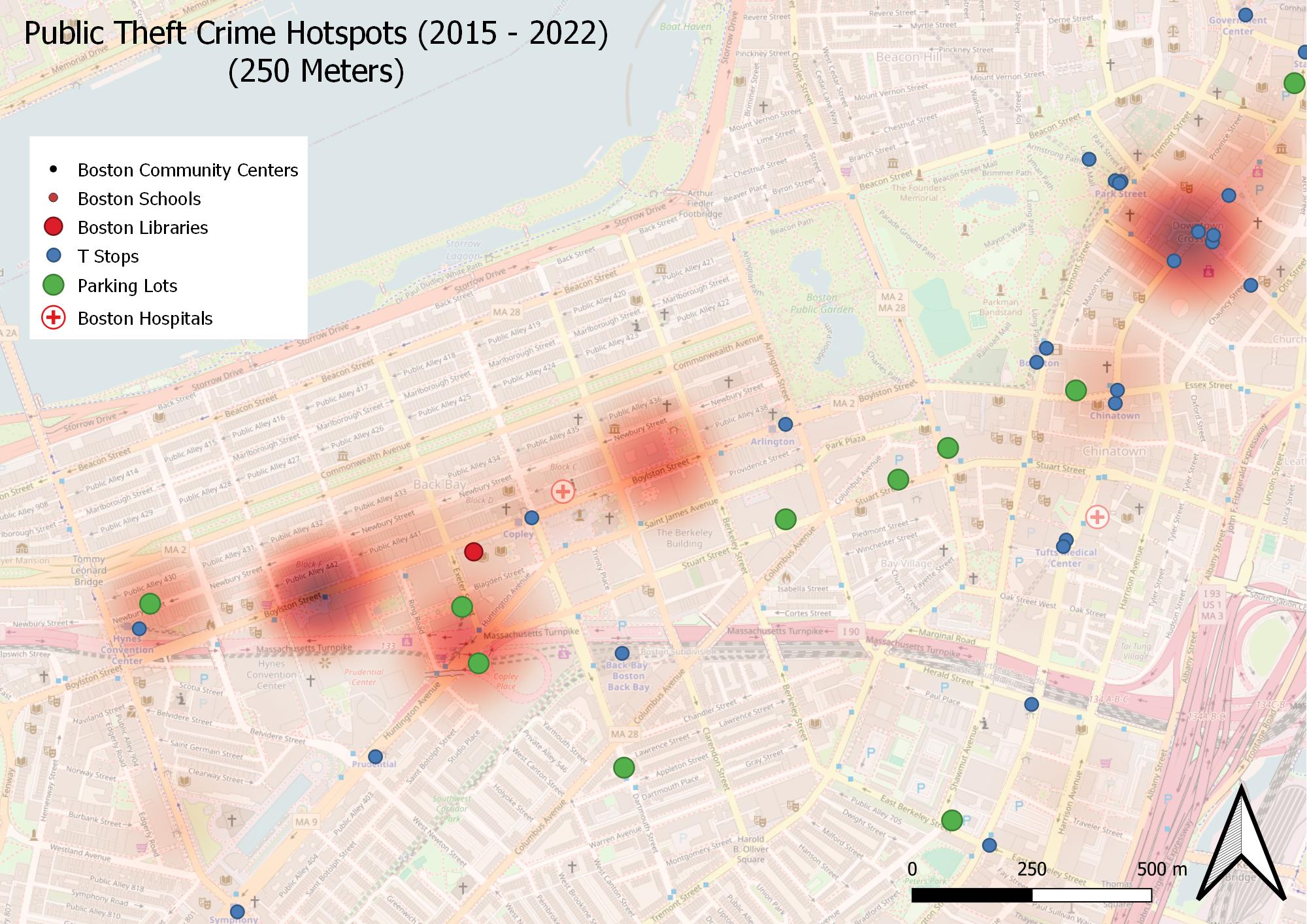

My general methodology when looking at hotspots is to start at the meso-level (somewhere

between 1 and 2 kilometers), which roughly responds to a neighborhood or district (at the city

level; this differs when studying crime in rural communities), and then drill/dial down to find

individual, micro-level hotspots. The heatmap above looks at theft hotspots that have a 250-

meter radius, so these are relatively concentrated areas. The heatmaps shown when combined

at the meso-level represent Boston’s most identifiable theft crime hotspot. Apart from this City

Center/Back Bay hotspot, theft is much more geographically spread out across the city. For this

reason, I decided to break this area down and look at theft at a more concentrated level.

There are four easily distinguishable hotspots, and a fifth less significant one, around the Hynes

Convention Center (furthest left). The most significant and concentrated is around Downtown

Crossing, which is not surprising as this has one of the highest concentrations of transit stops in

the city, reflecting the way in which the area is used. It is also largely pedestrianized, meaning

that it will in all likelihood attract and concentrate a larger number of people in it than a non-

pedestrianized area. Another significant factor in such areas relates to the types of

establishments that operate there. In Routine Activity Theory, one of the things which

contributes to an incident of crime is the lack of a capable guardian. Jane Jacobs who wrote, the

“Life and Death of the American City”, wrote about her time living in the East Village of New

York, and how she always felt safe because her neighbors knew who everyone was and what

they did in the neighborhood, and so had “eyes on the street”. For a long time, it was generally

thought that “eyes on the street” were synonymous with natural surveillance e.g., if a burglar

could be seen breaking into a house, they wouldn’t do so. However, it is now understood is that

it’s not just about having “eyes on the street”; those looking must have some investment in

preventing offenses from taking place. A shopworker, working in a chain or “big box” store, on

minimum wage has much less incentive reporting a crime taking place outside or near their

place of work than a business owner who knows that if potential customers stop coming to their

establishment due to a fear of crime they are going to be directly, financially impacted.

Persistent offenders understand when those in the areas that they offend in have little incentive

to get involved in stopping them. Both the Downtown Crossing and the Boylston Street hotspots

(especially the most concentrated one, located in front of the Prudential Shopping Center) are in

areas that house name-brand stores where the individuals working there aren’t directly

impacted by them becoming high-crime areas. This is not to say that this is the only reason why

these areas have become hotspots, however it is one of the factors.

The lack of guardianship in how certain areas become crime hotspots can also be understood in

reverse i.e., why crime rates are reduced in an area when guardianship increases. Whilst the

gentrifications of high-crime neighborhoods can have negative consequences, such as forcing

long-term residents – who were a stabilizing influence in the community – out, due to increased

housing costs etc., often one of the positive influences that such projects have is to bring in

small and private business enterprises such as restaurants, small grocery store owners and the

like i.e., individuals who will report crime, and act as the “eyes on the street” . Even new

residents, who have decided to “invest” in an upcoming neighborhood, attracted by the relatively

cheaper housing compared to other “safer”, but more expensive, areas they may have

considered, will want their property to increase in value, which will involve a reduction in the

crime rate. Such individuals may also find themselves acting as the “eyes on the street”, due to

their vested interest in seeing crime go down, not just due to personal reasons but due to

financial reasons as well.

Whilst an employee who has no financial stake in the company they work for (and this does not

account for all employees), may care about becoming the victim of violent crime, they may care

less about crimes they feel they can prevent or reduce victimization from e.g., if they know the

locale within which they work attracts many pick-pockets, they may believe that this is a crime

they will be able to avoid etc. In areas that attract a lot of suitable targets, its likely that area will

also attract a lot of motivated offenders, and without the presence of capable guardians (those

who have an active investment in reducing crime), it is likely for crime incidents to go

unchecked.

Share:

Gershon Ben Keren

2.8K FollowersGershon Ben Keren, is a criminologist, security consultant and Krav Maga Instructor (5th Degree Black Belt) who completed his instructor training in Israel. He has written three books on Krav Maga and was a 2010 inductee into the Museum of Israeli Martial Arts.

Click here to learn more.